The spectre of .hack hands me to this day. I often refer to years that initiate entire ‘eras,’ years where seemingly everything about me changes at the same time. It seems to occur every 5-10 years; the initial year was somewhere around 2004-2006. .hack//sign had been airing Friday nights. I dutifully followed the entire run, week after week, and mentioned pivotal episodes on a Livejournal — and when my cadre of friends moved onward to Naruto, seeing .hack as a kind of shonen sucralose, I didn’t really find much appeal in the endless child warfare so much as the strange and melancholy mysticism of human connection of what I had first seen.

The show is of course about Tsukasa, “trapped in the MMO”, who feels the game world as the real world. Linked inexplicably to a girl sleeping, waiting to be born, Tsukasa is tracked down by in-game societies and private player researchers trying to uncover why exactly he has a beast that can send other players into comas in the real world. Tsukasa doesn’t seem to know how he got there, let alone why everything feels so real, but everyone involved just manages to continually scare him, in this game world where their presences are existential threats. This existence is all he is.

I think they really wanted to make another Evangelion at the time; they had taken the same character designer, gone all out on a cross-media universe of mystery and lore, introduced all the same vague religious imagery with a timeline to a catastrophe that already occurred. If you grew up after Evangelion but before Crunchyroll, there’s a pretty good chance .hack ended up becoming your Evangelion anyway. It has never left my mind. I have written journal entry after journal entry in the fugues of my life trying to understand what I wanted from it. Why did I endlessly play the same MMOs searching for what was once represented in this one, tonally-solitary anime, this love-letter to Final Fantasy XI and Gainax?

I never really found it, after all. I often played them alone. I would role play, or passively interact with players in towns … I think the closest I’ve ever come was a fairly close guild of people in Guild Wars 2, way later in 2018.

But these experiences – this supposed interpersonal layer above the world, these games that “everybody plays,” where everyone is in new roles, finding each other yet again – these experiences I couldn’t find in reality. What was I yearning for?

The same year .hack//sign hit the air, All About Lily Chou-chou hit the theatre circuit.1 It was supposed to be this grand universe, too; an ARG taking place on the internet about a mysterious murder that unfolded around a Bjork-esque artist and all her devoted cultists. Eventually after being workshopped and workshopped, Shunji Iwai released it as an extended, novelistic film that instead focused on this parallel between the endless suffering of the real world and the transient, soothing state of the Ether.

Lily Chou-chou becomes a megami, a sort of compassionate demi-goddess, whose adherents expound a canon and theology around her work; what does she mean when she sings? From where did it come? What is producing all this feeling in us, how can we connect around it? Maybe in that respect she’s more akin to the Paraclete. She is the water through which the suffering souls can find their way to love.

In the meantime in the film our characters endlessly torture each other, or else silently take the blows of others, finding themselves impotent to do anything in the face of an enormous system of brutality recursively imposed by the ways each person has been hurt in their own lives.

I find the film very motivating and meaningful in the way a lot of visual novels are. It feels like in the face of all this suffering there is still endless hope, there is still the ability for things to heal, there is always a reservoir in which that softened self resides. My girlfriend when watching it had said it seemed more like those parts were simply dead and the Ether was the underworld to which they had been banished.

I am not so sure, though. In the turn of the century, the message seems ultimately optimistic to me? That is to say, the power of this overlaid world actually allows for reconciliation. In .hack//sign, reconciliation happens and the heart can heal; in Lily Chou-chou, the reconciliation doesn’t occur.

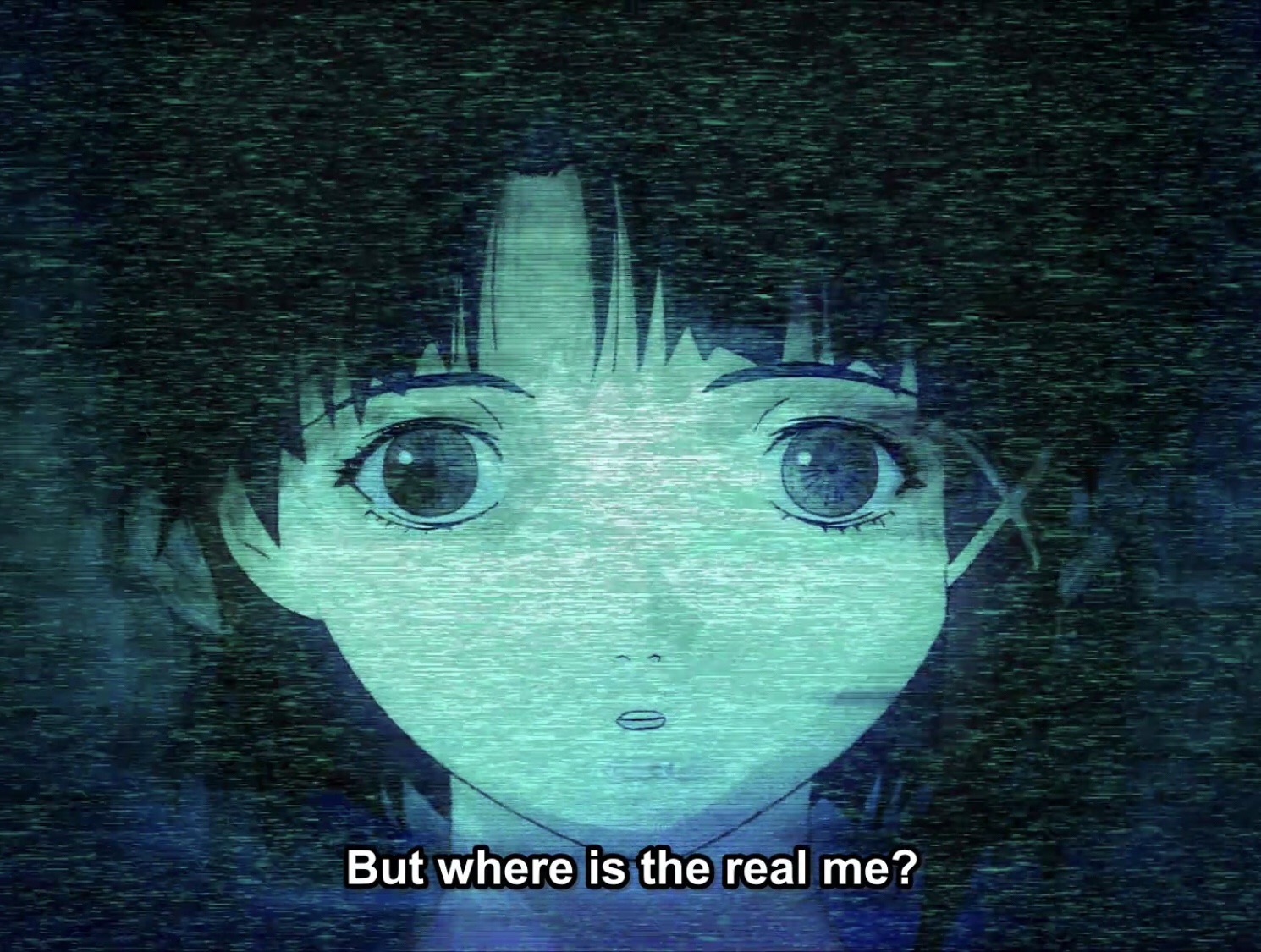

Is it more accurate to say that the physical vessel is the real self, or is it the blossom of selves that comes out of the wetware? I think on some level 2004 represented the juncture point where I could realise that I didn’t need to be everything this body implied. I could articulate different parts of myself that reached back into me, yearning for unity and coherence.

There was always the off-switch at the end of the day. Her life was still in his hands, wasn’t it? But when he tried to kill her off, the “result was horrific.” Suddenly the off-switch wasn’t there. Was he being used by the characters he typed? How long had this been going on? 2

In the reading I did on the Cybertext, Aarseth spends a chapter on MUDs, from which early MMORPGs developed, and which share a common ancestry in Dungeons and Dragons.3 In it we hit on the very same themes that once represented what video games were to me: self-expression while denying myself any in the real world, the creation of a (sort of) gnostic subordination of the flesh to my ‘real self.’

The use of anonymity, multiple nicknames, identity experiments (e.g., gender swapping), and a generally ludic atmosphere suggests that the participants are not out to strengthen their position in society but rather to escape (momentarily) from it through the creation of an ironic mirror society that will allow any symbolic pleasure imaginable. 4

This is the whole idea behind .hack//sign’s tangle of character drama: the mechanics of the game world itself bends to support the emotional walls and anguish of our protagonist; the purification of their toxic attachment culminates in the entire cast becoming family, lovers, friends in the real world. The game world gets left behind: it is somewhere purgatorial, liminal.

Here as elsewhere, the rhetorical figure of virtuality seems to suggest that MUDs are examples of a Derridean supplément, an addition to or expansion of the privileged modes of social interaction but at the same time an inferior substitute, a sinister dark-side consequence of modern technological society […] the long tradition of mediated social interaction suggests that MUD is not a peripheral phenomenon in the history of communication but can, instead, be read as a condensed paradigm of the types of rhetorical strategies that develop in nonlocal social systems. MUD is not the playground of a mythical literary language but the kind of playground that preconditions the awareness of textual identity in a much more effective way than previous such social technologies (letters, diaries, notes) could be, since the real-time nature of the social interaction puts the individual under a cognitive pressure that those other media typically lack. 5

If you imagine society as a machine (a “body” without etc. etc.) then you could imagine these Etheric worlds as parallel societies whose bodies are built out of the mechanics of their worlds mediating their interactions. After all, ergodic literature “produces symbols” as a symbolic machine; if MUDs and MMOs involve hundreds or thousands of people engaging in a larger machine, then it truly is a parallel world, albeit one with a more or less fixed state machine underlying the interactions that can occur.

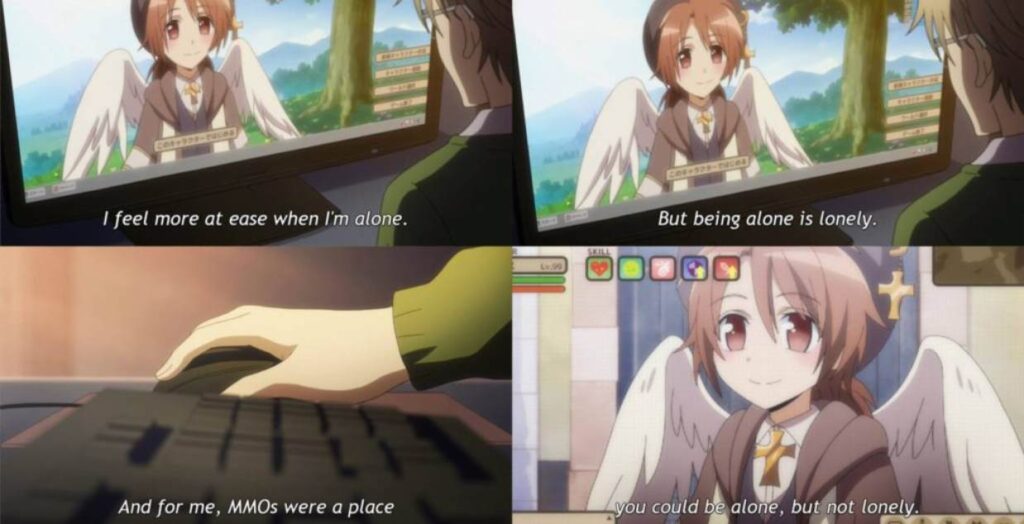

I was asked by a close friend recently if I had the chance to see Netojū no Susume (“Recovery of an MMO Junkie”); and I actually had seen it at release in December 2017. I remember I had a friend over as I was recovering from an operation and we just went through the whole thing together. I didn’t realise how much that anime would affect me at the time — I mean, I like heterosexual romance, but it never usually stays with me.6

In it, a career woman burns out at work and just abandons her life entirely, spending her days in the dark, crossplaying as a boy in an MMO, while living off konbini food. There’s no real pattern here; she’s just given up, ashamed of having left the job, of being incapable of dealing with the stress and the hours.

She makes contact with a healer girl, and well, it’s not that much of a spoiler that it’s a boy, a rather well-off boy, who makes contact with her heart and through their awkward romance inspires her to return to life.

The same patterns develop as we’ve seen before: the MMO world provides the amniotic fluid in which new things are born; by allowing something small to cultivate itself, something larger emerges.

This sequence is absolutely purgatorial: if hell is being apart from God — turned away from others and from love — then any place that allows one to slowly turn one’s head toward love is the limbo through which the heart recovers itself.

There is this last part that I think about all the time, and it’s when she visits the boy’s apartment and sees his computer. There is his keyboard, pink like all his devices; and there, on the screen, is the phenomenological viewpoint through which he came to love her, too. 7

How weirdly personal it is to see your lover’s “body,” to see through your lover’s “eyes,” through these prosthetics. I don’t know about you – I’ve done that before, scrutinising the “battlestation,” the strangely … delicate relationship of the machine to the body, of people I meet. Like I’m being trusted with something.

I think over my life I’ve come to understand that the liminal space, the space where the symbolic is in flux, can be anything — is necessary for transformation. It fascinated me the more I needed it, and I grieved it the more I “solidified,” needed to be made lighter and reformed again and again.

And so I’ve also come to understand that nothing about me is fixed; that love will use me however it wants in order to make itself known. Insofar as everything is fluid, everything is malleable, so too is all subject to what will bring me closer and closer and closer…

Does love therefore surpass being? How could one doubt this after the revelation of this truth through nineteen centuries by the Mystery of Calvary? “That which is below is like to that which is above”—and is not the sacrifice of His terrestrial being, accomplished through love by God Incarnate, is this not the demonstration of the superiority of love over being? And is not the Resurrection the demonstration of the other aspect of the primacy of love over being, i.e. that love is not only superior to being but also that it engenders it and restores it? 8

-

I’m not actually sure if it hit any theatres. ↩

-

Obviously, the Julie Graham case from Zeroes and Ones. ↩

-

Not entirely. Partially MUDs inherit from “adventure games” (which even now has metamorphosed as a generic term twice or three times over), but by the mid-1980s, downstream MUDs had arrived that definitely inherited system and scaffold from DnD. ↩

-

Aarseth, Espen J. Cybertext. John Hopkins University Press, 1997. Print. 144. ↩

-

Ibid, 146-149. ↩

-

Actually, come to think of it, My Dress-Up Darling stays in my mind a lot, too. ↩

-

I have always had this fascination with intermediated becoming, and ‘becoming’ as a process, that has taken me through Deleuze and Girard and even still I don’t understand it. To want to have x is to want to be a thing that has x; but to love y, does that involve at least a little bit becoming y? ↩

-

Meditations on the Tarot. 34 ↩